Isn’t music fascinating?!

Music is a universal language. Every culture has a form of music-making, and within that there are different ways of ‘recording’ or ‘noting down’ that music.

For example, in some cultures, music is taught and transferred by the oral tradition- meaning that music is passed on from generation to generation simply by listening and teaching. You don’t need to write anything down! You do it by memory. Think about the tune to ‘Happy Birthday’. Were you taught the music, or did you simply ‘pick it up’ from those around you?

Lots of notes

So, what happens when music gets more complicated? And, what about creating new music?

Check out this video below of a mammoth 40-part choral work written over 450 years ago by a man named Thomas Tallis. This choral work is made up of 40 singers, split into 8 different choirs. Each choir has 5 singers; soprano, alto, tenor, baritone and bass. In the video, each ‘choir’ is represented by their own colour (Choir 1 starts the piece, and they are in red). You can see how each line enters, and the shape of the notes they sing. Wait to see what happens 2.5 minutes in, when all 40 voices finally sing together!

But is this visualisation enough?

Have a think, as you watch and listen, about this question. Could the singers perform from using these lines below? Do they contain all the information they need? Is it clear enough? Is there anything missing?

We need more detail!

Details are absolutely key in good musical writing. You may have asked yourself, whilst watching the video, but what about the lyrics to this piece? How do they know whether to sing ‘loud’ or ‘soft’? What about ‘how’ they should sing- should it be ‘triumphantly’, or even ‘mournfully’?

Therefore, learning the universal language of musical notation is crucial when writing new music. There needs to be a way for you to communicate what you want your work to sound like, a way for singers to interpret the notes on the page, and a way for the Director to determine what you intended!

Music notation is probably the most logical international language ever created. So logical, and yet able to be manipulated to achieve any desired result. With it, we can write down any genre/style of music, be it ancient or modern and from any part of the world. The basics of music notation are often not fully explained, but they can be extremely helpful to budding composers, because good notation skills can free up your musical language and allow you to create exactly what you want. Learning a new language can be tricky and a real investment of time and study. Can we encourage you to persevere? Because the end result is absolutely worth it! Clearly constructed music, well communicated ideas, and structured and coherent writing is the only way to get your music out to as many people as possible.

Your Choral Compose guide to notation:

We’re delighted to bring you a selection of short and helpful materials from ORA Singers Chairman of the Board, Paul Max Edlin. Paul has a career that combines composing, conducting, trumpet playing, lecturing and artistic direction, and has generously put together a list of useful resources for aspiring composers below.

So let’s begin!

RHYTHM:

1) Musical note lengths

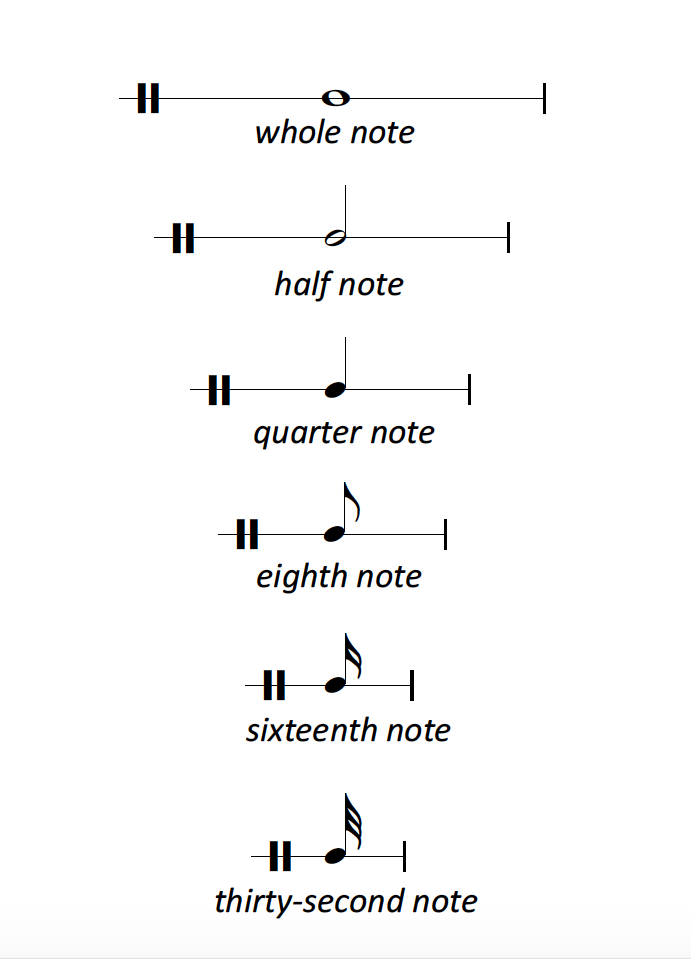

We have note values, which determine the length of a given note, from 'whole' (or even 'breves') notes to '64th notes'. This is what they look like:

And this is how they relate to each other:

2) Rests

It is important to remember that we don't have to have notes all the time. To be honest, we all like to have rests!

+ Find out more

To instruct a musician or singer not to play or sing, we create 'rests'. We also use beams in order to help group notes together, making it easier to see how a group of notes relate to the main 'beats' in the bar. We can use beams or 'tails', and we usually group notes together according to the time signature. For instance we would beam 4 sixteenth notes together in a 4/4 bar.

However, there are exceptions to the rule. If we had a single sixteenth note followed by rests, we would probably use a tail - but not always… Rules can be broken for good use!

Click on the button below to see more on rests, beams and tails!

3) Time signatures

Just as it is difficult for us to follow extremely long sentences in speech, it is difficult to coordinate voices and instruments in long passages with no visual aids. So the clever device called the 'barline' was created.

+ More on barlines!

Barlines divide 'bars', and these bars can be any length we choose. (In fact, we don't have to have them at all if we don't want to.) To determine the length of a bar we create 'time signatures' to subdivide 'musical sentences' and to explain how many notes can exist within a bar. We do this by putting two numbers on top of each other at the start of a bar or group of bars.

The lower number explains the note value you are referring to - i.e. a half note or a quarter note, etc. The upper number indicates how many we are including. Click the download button below to view some examples.

Want to put this into practice?

We speak to Paul about how to choose a time signature.

For a little more information on the different time signatures and metronome markings, and how you might choose between them, please click on the worksheets below:

4) Tuplets

Question: what do we do if we want note lengths that are 'in between' these? Answer: we create what are called TUPLETS.

Tuplets are note values that exist in proportion to other note values. The most obvious/common is the 'triplet'. A common triplet puts 3 notes in the space of two. This is a ratio 3:2. But we can create other logical ratios.

Do you see that this opens up a whole new range of possibilities? If we can have three notes in the time of two, why can't we have five in the time of four, seven in the time of four, or even six in the time of five? Yes, we can, but they can be hard to work out. Common ones are 5:4, 6:4, 7:4 and even 9:8.

Here are some examples of what can be done in ratios to four.

More/much more unusual ones are 5:3, 4:5, 7:5, 9:7, etc. But remember, it will have taken a musician a while to master the triplet, so please don't start creating complex mathematical examples that will require an experienced musician to 'go back to school' or a Director to experience a nervous breakdown!

Here are examples of other 'tuplets' - but be warned: do not make it too hard for your performers. What looks good on paper might just stay on paper!

5) Dots and double dots

While there are more things to learn, these 'basics' give you a comprehensive language, and an ability to notate pretty much any rhythm you choose. Just think how logical that all was- far easier than A Level Maths! Here is an example that uses everything we have covered:

There's just a couple more things to mention: dots and ties…

By putting a dot after a note or rest we add half as much again. And by adding another dot, we add another half as much again. Alternatively we can 'tie' notes together by putting an arc over them or under them:

6) Grouping notes together

We need to make music as clear as possible to performers. Performers need to be able to work together easily in order to produce the best and most professional result. It is important to group notes together sensibly. That is generally to group notes to align with the 'beat' of the bar. Aim to make your written music fit with with the time signature/s chosen.

+ Read more

However, it is important to mention that you can write without bar lines too and with beaming (and even speeds) that run independently. You can use your notational toolkit to create individual musical lines that can all look independent. In which case, just make your ideas clear and ensure people can know how to function together.

Always be ambitious, and if you are unsure about an idea, please talk with a composer/experienced musician. In the meantime, here are is a worksheet to help you...

NOTATION:

7) Notes

The way we write notes is brilliantly and simply achieved by using a stave - a simple set of five lines, which is easy on the eye.

Let's start with a simple scale of C, starting on a bottom C (two octaves below Middle C) and rising to Top C (two octaves above Middle C). Using the 'bass' (F) clef in the lower stave and the 'treble' (G) clef in the upper stave, we can indicate which notes we wish to use. Please see that Middle C sits comfortably exactly between the treble and bass clef (on a single ledger line)

It is lucky that this demonstrates the full range of a professional choir! Both Bottom C and Top C are very hard to get, so use them sparingly!

8) Naturals, Sharps and Flats

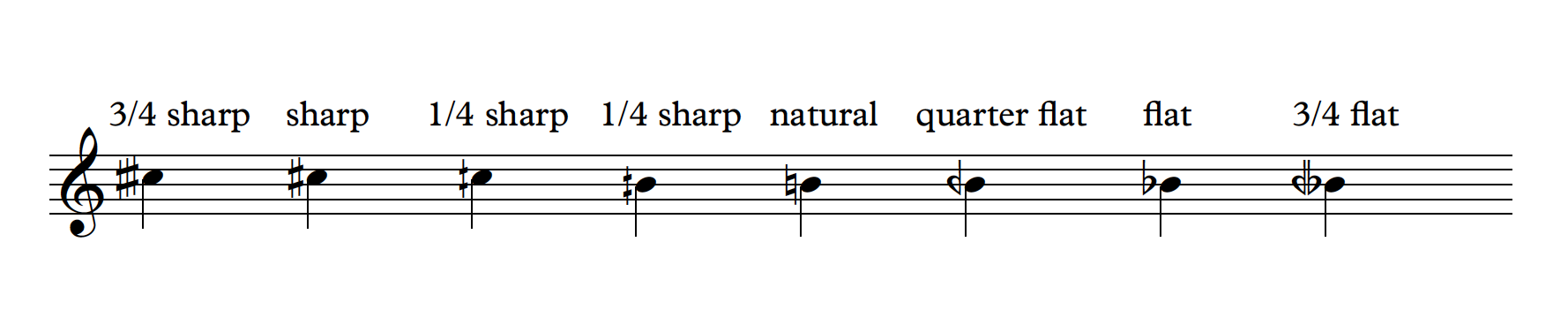

Then all we need to do is indicate whether a note is a semitone sharp or flat with appropriate signs (or if it's natural):

But we can also write notes between 'semitones', such as quarter tones, and these are conventionally written like this:

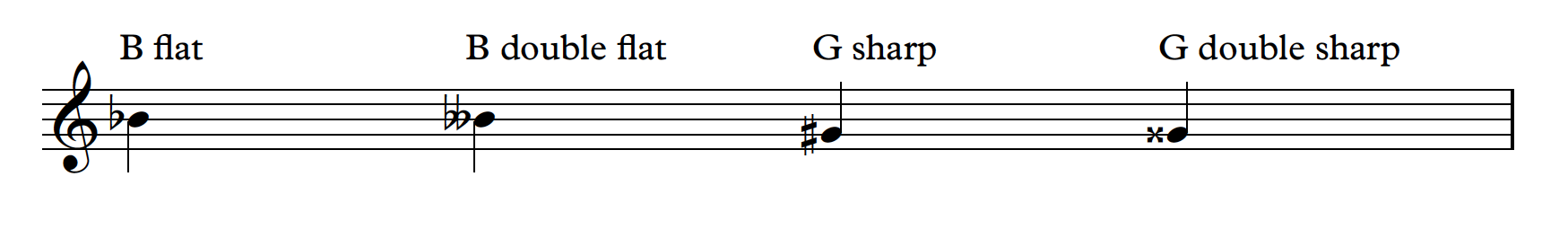

We may also need to have double sharps and double flats, especially in keys with many sharps or flats:

So, in effect, we have the following 'accidentals' available on each note (in this case ascending on G):

This is, essentially, all you need to know about how to write notes. Yes, it's that simple! But remember that it takes singers many years to learn to sing semitones in tune, so please use quarter tones carefully!

9) Tonality & Atonality

Should we compose in keys or should we avoid them? This is up to every composer. Some novelists like to set their stories in times past, while others write about today or tomorrow. Whatever we do, we need to make sense.

There are a whole set of established ideas when it comes to writing music in keys - i.e. tonal music. In the Twentieth Century all these methods were redefined or ignored, and a whole series of new ideas were established.

If you want to write in keys (i.e. tonal music), then the Circle of Fifths is important to study. It makes perfect sense, and this is what it looks like. As you go clockwise round the circle, you count up 5 notes (a perfect fifth) and land on your next key. In the process, an accidental (a sharp or flat) gets added. You will see in this way how keys are related. For example, starting at the top in the key of C, which has no sharps or flats, counting up 5 notes brings you to G (c-d-e-f-g) and adds a sharp. And counting up 5 notes from G brings you to D, and adds another sharp.

The basic toolkit for notation runs independently from ideas to do with tonality and atonality. If you want to write tonal music, you really need to understand the language properly and be able to use it fluently. If you want to write atonal music, then you still need to know what you are doing, be consistent and coherent, and you need to write from both head and heart.

Whatever you choose to do, whichever path you prefer to travel, the established system of notation will give you all you need to know to get cracking!

There are many books and online resources for you to explore. So get exploring and get creative!

Other considerations

DYNAMICS:

Be sure to give details about the dynamics you want. If you want very loud then use 'fff' or 'ff'. If you want your music very soft/quiet, then use 'ppp' or 'pp.’. To find out more, try this Wikipedia entry.

METRONOME MARKS/SPEED INDICATIONS:

It is always important to indicate the speed you want. Use metronome marks and explain if you want to slow things down or speed things up. Metronome marks are so easy to understand. Just indicate the note value of choice and tell us how many there are in a minute.

For instance 'quarter note' = 60 simply means that there are 60 quarter notes in a minute (i.e. one per second!). 'Eighth note' = 92 simply means that there are 92 eighth notes in a minute. And if you don't want to use Italian terms, then use your own language. If you speak English, why not write 'Fast' - or 'Fast, with energy'. We recommend reading this article to find out more!

PHRASING & EXPRESSION:

Make phrases clear and use marks to express the character you want. That may be accents, or 'tenuto' marks, etc. For far more comprehensive information about musical symbols and markings, try visiting this link.